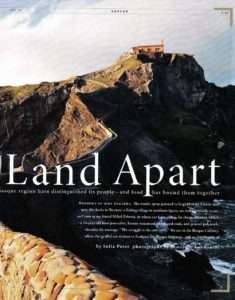

For centuries, the language and culture of Spain’s Basque region have distinguished its people—and food has bound them together

By Sofia Perez

[Published by Saveur, May 2007]

Borroka da bide bakarra. The words, spray-painted in bright red on a white wall near the docks in Bermeo, a fishing village in northern Spain, are indecipherable to me, so I turn to my friend Mikel Zeberio, in whose car I am riding, for the translation. Mikel, a 54-year-old food journalist, former restaurant owner and cook, and general polymath, decodes the message: “The struggle is the only path.” We are in the Basque Country, where the graffiti are written in Euskera, the Basque language, and are hardly ever of the “Joe was here” variety.

Borroka da bide bakarra. The words, spray-painted in bright red on a white wall near the docks in Bermeo, a fishing village in northern Spain, are indecipherable to me, so I turn to my friend Mikel Zeberio, in whose car I am riding, for the translation. Mikel, a 54-year-old food journalist, former restaurant owner and cook, and general polymath, decodes the message: “The struggle is the only path.” We are in the Basque Country, where the graffiti are written in Euskera, the Basque language, and are hardly ever of the “Joe was here” variety.

Technically, this part of the world is in Spain, but it’s definitely not of Spain. In some towns, you could pick a fight in under a minute simply by referring to the locals as Spaniards. Until the debut, ten years ago, of Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, the architectural marvel that initiated the transformation of that city from industrial center to tourist destination, it was rare to see an international news report covering the Basque Country that wasn’t about Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (Basque Homeland and Liberty)—the Basque separatist group commonly known by its acronym, ETA—and its violent battles with the Spanish authorities.

But Euskadi (the Basque people’s name for their homeland), a place that the locals often refer to in Spanish as their pequeño país (little country), has much more to offer than troubles, not least of all its food. I could not have asked for a better guide to the region and its cuisine than Mikel, whom I met a few years ago through a mutual friend who is a chef in San Sebastián. A bear of a man, though decidedly more teddy than grizzly, he is a walking encyclopedia of Basque food and wine.

Although the three Basque provinces of Bizkaia, Gipuzkoa, and Araba (as Vizcaya, Guipúzcoa, and Álava are rendered locally) have been part of the Spanish state for more than five hundred years, people who consider themselves Basque have been living in the mountainous, northeastern corner of the Iberian Peninsula for more than two thousand years. The Basque homeland—an area not much larger than Delaware, with a population of roughly 2 million people—had one of the earliest democratic law codes, known as the fueros, and people here pay all their taxes to the provincial government, which forwards a portion of the revenue to Madrid. Further distinguishing the Basque Country is the fact that the Euskera language bears no resemblance to any of the Romance tongues spoken in neighboring countries; philologists are still arguing about its origins. “Our language is the connective thread that has helped this little country survive,” says Mikel.

When it comes to conversation, whether it’s in Euskera or in Spanish (in which all Basques are fluent), people here address a holy trinity of topics: politics, soccer, and food, though not necessarily in that order. The region is home to a plethora of Michelin-starred restaurants specializing in haute, ultramodern cuisine, but the most common debates center on how to prepare traditional Basque dishes. Seemingly everyone has an opinion because just about everyone here cooks, including—and especially—men, in sharp contrast with the rest of Spain. Basque women still rule the home, but the men have established their own enclaves, places where they can connect over food and drink and where they are the ones in charge of the flames.

***

The table is set for dinner at the Doniene winery (Photo by Sofia Perez)

A few days after I arrive in Bilbao, Mikel gathers a group of friends at Doniene Gorrondona Txakolina, a small winery, in the coastal town of Bakio, that is known especially for its white txakoli (pronounced CHA-ko-LEE), a young, dry, mildly sparkling wine made from hondarrabi zuri, an indigenous grape. Mikel is multitasking in the kitchen, cooking several dishes, among them a hearty potato and leek soup known as porrusalda, while his 60-year-old friend Kepa Freire, who runs a smoked-fish company, acts as his sous-chef, stopping every so often to regale me with stories on local culinary history. “Traditional food here means everything,” Freire says. “The rest is just a lie.”

Meanwhile, Andoni Sarratea, a 38-year-old who is one of the winery’s co-owners, has drifted into the room and is egging Freire on in a discussion of whether or not bacalao a la bizkaina (a salt cod recipe that features a sweet pepper sauce) should be made with tomato or not, a long-standing dispute. Freire takes the bait: “Using peppers alone can make the dish bitter.” Mikel shoots him a stern look, stops what he is doing, and carries over a pot of his tomatoless bizkaina sauce. “Taste,” he orders Freire, as Sarratea stands next to them, making no effort to conceal a grin. Freire dips his index finger into the pot and then raises it to his mouth. All eyes are on him. After a pause, he launches into a story about what a great cook his mother was, not so deftly avoiding an admission of defeat. Sarratea erupts into laughter, and Mikel returns to the stove.

Later, Mikel takes me to the small city of Mungia, where he and Freire prepare a multicourse feast for ten in Freire’s txoko (pronounced CHO-ko), one of the private, dues-paying, all-male gastronomic clubs of which there are scores throughout the Basque Country. Here, in an establishment co-owned by all the members, the men set a long wooden dining table, and those who are not manning the stoves in the restaurant-grade kitchen mill around, observing and offering their two cents. “I make mine a little differently,” says Pedro Prieto, a friend of Freire’s, as he leans over a pot of Mikel’s marmitako—a savory tuna and potato stew brightened with mild peppers called choriceros—bubbling away on the stove.

In addition to the marmitako, Mikel cooks up a rich, dense garlic and bread soup using zopako, a dried, rusklike bread produced in the Basque Country specifically for use in long-simmering dishes. Slightly charred on the outside, the zopako absorbs the concentrated flavor of the garlic and chicken stock and gives the finished soup a comforting, pillowy texture. Seeing everyone enjoy the food, Mikel smiles at me and says, “Cooking for your friends is truly one of the great pleasures of life.”

For dessert, Freire makes tortillas stuffed with dark chocolate—a dish known as talos con chocolate—using finely ground cornmeal that Mikel and I have purchased earlier from Luis Azillona, a miller (see page 86). The kernels that Azillona uses have been toasted before they are ground; the process yields an earthy, smoky flavor that enhances the dessert’s bittersweet filling.

***

Demetrio Terradillos grilling chuletas (Photo by Sofia Perez)

In virtually every place where Mikel and I travel, the tradition of men gathering over food and drink is reenacted again and again. At Urbitarte, a cider house and restaurant in the town of Ataun, in Gipuzkoa, where apples have long been an important crop, we join Mikel’s cousin Juantxu Zeberio and a group of his closest friends, who meet here every Tuesday night in a venerable communal ritual that has experienced a resurgence in recent years. “Txotx!” yells Demetrio Terradillos, the ringleader and also the chef; the word (pronounced CHOTCH) in this context refers to the wooden stick once used for plugging the hole of a hard-cider barrel. Terradillos’s call is the signal that a jet of the fizzy amber beverage is about to be released. In unison, everyone rises from the tables, tumblers in hand. At the barrel, each person bends forward in turn, lowering his or her glass almost to the ground to catch the arc of cider, and follows the stream to its source (the motion is designed to aerate the cider and create more fizz). No one wears his or her best shoes to a cider house meal.

The menu rarely varies: there is a bacalao (salt cod) omelette, fried bacalao with peppers, enormous beef chops (grilled and sprinkled with coarse salt), and, for dessert, walnuts, Idiazabal (a local sheep’s milk cheese), and apple jelly. In the cuisine of the Basque Country, many of the same ingredients appear repeatedly in almost innumerable but subtly nuanced variations. “This place is aesthetically beautiful, but its riches are measured,” Mikel says. “Because of the humidity and the harsh landscape, it’s never been an easy place to farm.”

Given the Basque region’s connection to its coastline, which stretches for more than 150 miles, fish are an important part of the local diet, and the fishing and canning industries dominate community life in many coastal villages. In the Bizkaian town of Ondarroa, Mikel introduces me to José Antonio Aguirreoa, head of Conservas Aguirreoa, a fish canning business started by his grandfather in 1888. As we walk through town, he points to the church steeple and to a metallic object perched near the bell. “That siren goes off whenever fishing boats return to port, letting everyone know what they’re carrying: one ring means tuna, two for sardines, and three, anchovies.”

Though geography and weather may have conspired to limit the local larder, the Basque culinary imagination is anything but restrained. People here have found a way to create grand dishes out of very little. A case in point is bacalao al pil-pil, a dish that Mikel teaches me to make the next evening. It calls for nothing more than skin-on salt cod, olive oil, garlic, and, if the cook is feeling bold, a guindilla—a skinny, green, mildly piquant chile. Warming the fish slightly in a small amount of garlic-infused olive oil, Mikel takes the skillet off the heat and then, shaking it regularly, adds more oil, a little at a time, until it emulsifies the gelatin released from the cod’s skin. The result is a thickened, almost opaque golden sauce that softens the pungency of the garlic and the briny tang of the salt cod, producing an elemental fusion all its own.

***

From Ondarroa, Mikel and I drive inland, toward the mountainous Bidegoian district of Gipuzkoa Province, where we meet 36-year-old Pello Urdapilleta, who lives with his wife, mother, and two small children in his ancestral home. In a place where language is identity, a name can mean everything, and in the case of Urdapilleta, it became his destiny. When his father died, the 19-year-old Urdapilleta decided to put together a genealogical chart. Tracing his surname—which literally means pig pile—he discovered that his family tree had pig-farming roots in the area going back at least as far as 1575. Eight years later, he read a newspaper article about the disappearance of two of the three indigenous types of Basque pig and, after asking around, found that the remaining breed, the euskal txerria, was also on the verge of extinction. Given his own family’s historical ties to pig farming, he vowed to try to ensure the breed’s survival, visiting area farmers who had a few of the animals left and buying as many as he could find. Over time, he and his brother Roke raised a small herd of these spotted creatures known for their long, floppy ears. The siblings now have more than a hundred pigs in their own “pile”.

The animals spend much of the year outdoors, feeding on grass, wild herbs, and the nuts of beech, chestnut, hazelnut, and walnut trees, a diet responsible for the complex, nutty flavor and buttery texture of the hams and charcuterie made from their flesh. The meat is different from, but comparable in quality to, the more famous pata negra pork products that come from Spain’s Extremadura region, in the southwest. Though Urdapilleta is not trying to compete with that larger, more established industry—right now, his venture is simply a demanding hobby (he works full-time for a meat company in a nearby town)—he hopes to make his living from it someday.

Later, we sit down to a lunch of spit-roasted, crisp-skinned chicken topped with bits of fried bacon along with plates of euskal txerria ham and salchichón sausage that Maite, Urdapilleta’s wife, has set out. Being able to preserve a part of Basque heritage has been rewarding, he tells me as he refills my glass, but he insists the source of his satisfaction is deeper than that. “The best thing about this work, the thing that makes the most sense to me,” he says, “is being able to share it with people seated around a table, like this.”

###

[sidebar] The Miller’s Son

In much of Spain, corn is used mostly as animal feed, but in a few northern areas, including the Basque Country (see page 64)—where it was a subsistence crop during tough economic times—it’s more widely consumed. In the small town of Gamiz-Fika, Luis Azillona, a third-generation miller and retired engineer, grinds a local variety of toasted corn using the tools and techniques of his ancestors. Covered with fine cornmeal dust, he took a break to chat with me during my recent visit.

How long has corn been grown in the Basque Country?

It first arrived here from the Americas in the 16th or 17th century. In small villages near Mungia, like this one, there were periods when corn was eaten three times a day.

Do you still get your corn from local farmers?

Yes, though there are fewer of them than in my grandfather’s era. I weigh the kernels and take a small percentage as my fee; that’s the way it’s always been done. Sometimes farmers grow more corn than they need, and if it’s of high quality, I buy the surplus, grind it, and sell it to txokos [private gastronomic clubs], restaurants, and retailers.

How often do you cook with cornmeal?

Two to three times a week in the winter. When it’s cold, we’ll sometimes make sarteneko: you fry bacon, salt pork, and chorizo to render the fat and then wrap the meat in a talo [a handmade corn tortilla]. I also like to dip the talo into the drippings left behind in the skillet. It’s wonderful for your blood pressure and cholesterol [he laughs].

Any plans for the future?

I hope to set up a small museum here. I’ve drawn up my will so that after I’m gone, this place will be maintained and these traditions can endure. —S.P.

###

[sidebar] Jagged Edge

Cooks tend to cut vegetables into nice, even shapes. But recently my friend Mikel Zeberio (see page 64) reintroduced me to a technique that my mother taught me years ago. When preparing potatoes for the Basque stews marmitako and porrusalda, he cuts the tubers into irregular chunks called cascadas; the word derives from the Spanish verb cascar, meaning to crack. Holding a potato in one hand, he inserts a knife partway into its flesh and twists it to break off briskly one jagged piece after another. According to Mikel, the cascadas’ roughly hewn surface releases more starch—which thickens soups and stews—than an evenly cut slice would. It’s easy to master; you could even say it’s a snap. —S.P.

###

[sidebar] The Guide: Basque Country

*WHERE TO STAY*

CASTILLO DE ARTEAGA Gaztelubide 7, Gautegiz-Arteaga (94 627 0440; www.panaiv.com/ingles/castillo /castilloarteaga.asp). Rates: $160–$190 double. Housed in a restored castle, this stunning, 14-room hotel is a peaceful yet elegant retreat. Relax on the roof deck while enjoying views of the lush, green countryside.

HESPERIA BILBAO campo Volantín 28, Bilbao (94 405 1100; www.hesperia-bilbao.com). Rates: $85–$225 double. Rooms at this mod hotel, centrally located on the Nervión River, are minimalist in design but comfortable. Reserve one that faces the water, and take in the shimmering lights of the promenade at night.

*WHERE TO EAT*

ARBOLAGAÑA Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao, plaza del Museo 2, Bilbao (94 442 4657). Moderate. This elegant restaurant offers a blend of strong, accessible flavors and haute cuisine refinement. Chef Aitor Basabe is an avid fisherman, and his seafood dishes—like flaky, moist machote (red porgy) served with a squid ink risotto—are particularly good.

BASERRI MAITEA Atxondoa, Forua (94 625 3408; www.panaiv.com/ingles/ baserri/baserrimaitea.asp). Moderate. Located in a traditional caserío (farmhouse), this restaurant serves up wonderful smoke-tinged fare, such as pichón (squab) and chipirones (baby squid), straight off the grill, but the other menu options, like a rich seafood soup studded with clams and shrimp, are more than their equal.

KAIA KAIPE General Arnao 4, Getaria (94 314 0500; www.kaia-kaipe.com). Expensive. At this split-level eatery, you’ll enjoy the freshest-possible seafood and an impressive list of Spanish wines. Don’t miss the txangurro al horno, succulent spider crab meat simmered in an aromatic txakoli (a white wine) and tomato sauce, then lightly baked in the crustacean’s carapace.

MUGARITZ Otzazulueta baserria, Aldura aldea 20, Errenteria (94 352 2455; www.mugaritz.com). Expensive. Specializing in neither molecular gastronomy nor rustic country fare, Mugaritz steers its own course with austere but exquisite creations, such as a roasted red mullet filet served with an ethereal saffron and rockfish reduction and a milk-flavored ice cream with tapioca pearls and hazelnut tuiles.

RESTAURANTE GUGGENHEIM BILBAO avenida Abandoibarra 2, Bilbao (94 423 9333; www.restauranteguggenheim.com). Expensive. Gehry’s building will engage your mind, and this restaurant will stimulate your stomach with memorable dishes like veal confit in a scallion–garlic broth topped with crisp, thyme-infused bread crumbs and a calabaza–bergamot custard served with heady beer ice cream.

URBITARTE Ergoiena Auzoa, Ataun (94 318 0119). Inexpensive. The classic cider house menu of bacalao, beef, and cheese provides a perfect counterpoint to the fizzy fermented brew that comes streaming out of the kupelas (barrels)